YA, romance, and sexism within the literary world

*some mature content discussed*

November 1, 2020

I love reading. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been devouring books at an alarming rate, and there’s nothing I like to talk about more than my current read.

But when people ask me what my favorite genres are, sometimes I’m not entirely truthful. When I say I like YA and romance, people tend to make snap judgements about my character, personality, and intelligence.

“I feel like a lot of people might judge you for liking things that are romantic. When I read the Hunger Games, I really liked the romance, but I told people that I liked the violence because I thought that’s what they wanted to hear. There’s definitely a stigma—when you tell people you like romance they think it’s weird—but that’s what a lot of people like reading,” says Sophie Evans (‘21).

This experience of being judged for my reading choices isn’t just in my head.

The more I talk to other readers of YA and fantasy, the more I’ve realized that they feel the same judgement I do. There’s a stigma surrounding YA and romance novels that simply isn’t there with other forms of genre fiction.

“Yeah, I definitely feel judged and feel embarrassed with what I’m reading. It’s what I like, so it’s what I read, but when I walk around at school, sometimes I’ll turn the cover around so no one can see it,” says Ela Kulkarni, (21).

I don’t exclusively read YA and romance—I like fantasy, science fiction, and steampunk, as well.

But most of the time, these genres don’t portray women in a very positive light, if they have female characters at all. Trying to find female-led fantasy can be like trying to find a needle in a haystack.

If you’re a fan of fantasy, you’ll probably recognize some of the most prolific writers of the genre: J.R.R. Tolkein, George R.R. Martin, Robert Jordan, Brandon Sanderson, Terry Brooks… I don’t know about you, but I’m starting to notice a theme.

Compare that to some prolific YA and romance authors, and a pattern starts to emerge. “Sophisticated” genres like fantasy and science fiction are incredibly male-dominated, while “lesser” genres like YA and romance are written mostly by women.

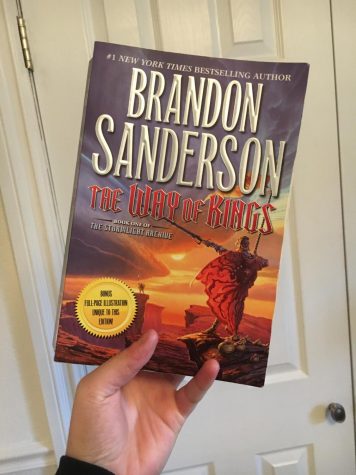

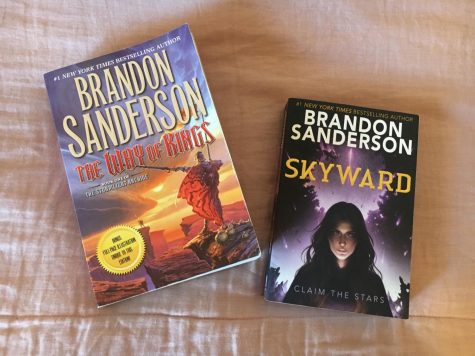

Recently, I read The Way of Kings by Brandon Sanderson after a recommendation from a friend of mine.

I had just finished Skyward, one of Sanderson’s YA novels, which had a wealth of strong female characters and a plot that engaged me from the very first page, so I was interested to see what The Way of Kings had in store.

The book itself was very interesting—Sanderson’s world-building is truly incredible, and even at 1,200 pages, the story managed to keep me engaged the entire time—but I had some complaints. Specifically about the representation and portrayal of the female characters in the book.

The book switches point of view between multiple characters throughout the novel. Although five or six characters get to tell their point of view throughout the book, only one of them is female.

The book takes about one hundred pages to pass the Bechdel test, and for certain sections—some of which are hundreds of pages long—the lone female character doesn’t have a single chapter. Of the characters in the book with their own point of view, she’s probably the least relevant to the wider story.

Brandon Sanderson also details gender roles unique to his world, in which men are warriors and women are scholars.

This is an interesting portrayal, and it gives the female characters a limited amount of agency, but none of them break from this gender role. Although these gender roles are interesting, they still feel restrictive when it comes to the women in the story.

I found it interesting that in Sanderson’s YA novel, the main character was a powerful woman, where in his fantasy novel, he hardly included any women at all.

But upon further examination, this is a theme in fantasy novels. Some of the most famous fantasy novels don’t represent women positively at all.

The Magicians by Lev Grossman is so wildly misogynistic at points that it makes my skin crawl—it has one significant female character who is defined only by her relationship with the main male character, and she is killed off at the end of the book; plus almost all of the female characters are described using only their hair color and the size of their breasts.

George R. R. Martin’s gross oversexualization of Daenerys—who, at the time, is a thirteen year old girl—made me so deeply uncomfortable that I couldn’t finish the book.

“When there are female characters in fantasy novels, the strong female character has to put down other female characters to be strong. She’s never allowed to like things that are feminine, or even get along with other women. She has to act like she’s superior,” says Evans.

If you walk into a used bookstore and browse the fantasy section, you’ll find rows of mass market paperbacks by male authors about male main characters.

You’ll also probably encounter a few dudebros wondering if you’re a “real” fan of the genre, or if you’re just reading it to impress men. Of course, there are a few wonderful female fantasy writers, but they’re largely the exception, not the rule.

“A lot of times, there’s definitely a set archetype of what a woman has to look like in fantasy. She’s pretty weak compared to the male counterpart. She’s not allowed to be as dominant or aggressive as the men in the story,” says Kulkarni.

Compare that to romance novels. Romance is the most successful genre in the publishing business, and it’s the only genre that is almost exclusively targeted towards women.

Like most genres, romance varies widely in terms of its plot and messaging—but a common theme in romance novels is women discovering their power and sexual autonomy. The romance genre is an enigma: it breaks down societal expectations of women as demure and “pure,” while still following the narrative of women in romantic roles.

It doesn’t push boundaries enough to be revolutionary, but it still doesn’t fit men’s image of what women are supposed to be. This, combined with its popularity, makes the romance genre a threat.

The romance genre is also ridiculed because of its content—specifically, love stories. Why is this? The same reason that some women are ashamed to admit that they like the color pink.

Romance is seen as something “feminine,” and in our society, “feminine” is seen as wrong. But in reality, there’s nothing inherently less important, emotional, or sophisticated about romance novels or wanting to fall in love.

Creating a great love story actually requires an impressive mastery of character development, and a lot of plot-driven fantasy novels don’t manage to expand upon their characters as more than one-dimensional plot devices.

“Gender roles say that women are the ones obsessed with love, and if a man reads a romance novel, he’s judged for it. Men aren’t supposed to be into gushy, emotional stuff, which in and of itself ties to pretty misogynistic ideals,” says Evans.

There’s also a fairly negative assumption about women who read sex scenes—specifically, that they’re lonely and desperate. But this is a double standard in the literary world. When fantasy novels written by and for men contain sex scenes, it never makes the book less “literary.”

A Game of Thrones is a great example of this. Although this series is littered with explicit content, one scene in particular stands out.

In it, thirteen-year-old Daenerys is graphically assaulted by her thirty-year-old husband, and the way the scene is written, it is painfully obvious that the reader is meant to derive some sort of excitement from the image.

The language and descriptions, along with the implication that Daenerys “wanted” it, are only a few of the reasons that I had to put the book down.

But that doesn’t really count as a sex scene, right? Even if it’s written graphically for the pleasure of the male reader, it goes towards establishing the main character’s trauma. A sex scene that the female character consents to or enjoys characterizes her as desperate, clingy, needy, and sexually deviant, doesn’t it?

Yeah, that’s another argument I’ve heard quite a lot. Sometimes it’s only implied, but sometimes it’s explicit that this is how readers view women.

For whatever reason, men view sex scenes as less “literary” if they’re between two consenting adults. If a female character in a novel enjoys sex, it ruins her “pure” image, and if a female reader likes reading sex scenes, she’s rebelling against society’s expectations—and she’ll be labeled as all sorts of ugly things for it.

“They’re reprimanding women for writing fairly tame sex scenes, so it’s messed up that men don’t face the same judgement. If you’re clingy for writing a sex scene—I don’t get that. It’s what a lot of people like to read,” says Kulkarni.

Of course, there are plenty of romance novels where relationships are creepy or predatory. However, from my experience, the romance genre is the only genre that is consistently judged for its worst parts instead of its best.

I’ve read many more misogynistic fantasy novels written by men than misogynistic romance novels written by women, but somehow only one of these genres is defined by the work of a few authors.

Additionally, lots of romance novels deal with very real overarching themes such as overcoming trauma, recognizing healthy versus unhealthy relationships, dealing with mental health, and more.

So, what about YA? Young adult novels have a bit of a reputation for being trashy, and I see where this comes from—I’m looking at you, Twilight—but the genre has evolved in recent years.

Instead of tragic vampire romances, there’s currently an emphasis in YA on sweeping, world-building fantasies, and as the genre has grown, the writing in these books has become more and more proficient.

Now, I find the writing in YA novels comparable to that of some fantasy novels I’ve picked up over the years.

I can’t argue that YA novels are more complex than adult novels, because a lot of them aren’t. There’s definitely trash in the genre, just as there is trash in all genres, and in the end, YA is aimed towards teenagers.

But YA is another genre that is predominantly occupied by female writers and female main characters. This means that it’s a decent alternative to fantasy for people who care to see women with strength and autonomy.

I think the number one reason why YA novels are seen as the lowest of the low, though, is because they’re popular amongst teenage girls.

I don’t think many groups are as consistently made fun of as teenage girls, from adults, boys, even from other girls trying to distance themselves from their peers to feel superior.

“As a teenage girl, you’re always trying to impress somebody. You feel like you have to prove that you’re worth it. In terms of how you look and stuff like that, or what your interests are, you’re always going to be judged for one thing or another,” says Kulkarni.

If teenage girls like something—whether it’s a book, a band, an activity, a trend, or a movie—it will almost definitely be viciously made fun of and torn apart.

“I really like the Vampire Diaries, One Tree Hill, and all those kinds of shows. People definitely judge me for that. I even liked One Direction and things, but when girls I knew talked about them, people would always judge them for it. They’d say its a ‘girl thing’ to be obsessed with One Direction, and if it’s a girl thing it must be bad,” says Evans.

Don’t believe me? Well, every guy who thinks he’s intellectually superior for listening to The Beatles should definitely know that they were popularized by teenage girls, who were made fun of for liking them.

Misogyny is still very much alive and well in the literary world. So, how do we fix it? First of all, we need much better standards for measuring female representation in a novel. We also need to start calling out sexism when we see it.

We need to stop viewing YA and romance as lesser genres, and most importantly, we need to encourage female writers in the fantasy genre.