So the police should be defunded…what would that mean?

As the demands for justice ring across the nation, activists and everyday citizens call for the police to be defunded.

August 20, 2020

For all that defunding the police can be debated, what it boils down to in the end is this: violence at the hands of the police has reached a point that, as human beings and citizens of a country sworn to protect us, we cannot ignore.

As extreme as it sounds, defunding the police is necessary for cities across the US that spend a disproportionately large sum of money on their police than any other essential department.

Why is this necessary?

The world has watched, for months now, what historians are calling the largest civil rights movement in history, sparked by the death of George Floyd, a black man, at the hands of a white cop.

This murder shook the world, and the video of police officer Derek Chauvin kneeling mercilessly on Floyd’s neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds went viral on social media. But the reality is that in 2020 alone, the police have reportedly killed 598 people in the US. 28% percent of those people were black, despite the fact that their race only makes up 3% of the American population.

The often-cited statistic that 50% of all crime in the country is committed by black Americans in spite of their small population serves to do nothing but strengthen the need for police upheaval. That statistic is based on police arrests; as long as the police remain unpunished for their racial biases, they can continue arresting people for petty crimes at will.

In an interview with Tufts Now, assistant sociology professor Daanika Gordon reported that “police leaders intentionally devote more resources to protect and serve the downtown and middle-class neighborhoods. Elected officials, business owners, and empowered residents demand police service, and police officials comply because these areas were seen as vital to the city’s economic health.”

Black neighborhoods are not considered to be vital to the economic health of a city, so they are instead, as Gordon says, “overlooked as areas meriting further resource commitments, on the one hand, and positioned as criminal threats to be controlled and contained, on the other.”

Put simply, black neighborhoods are overpoliced. The rates of crime, therefore, will seem higher.

Even without taking into account the horrifying reality of police violence, especially against people of color, data shows that 9 out of 10 calls for service are for nonviolent situations.

But because police officers are trained to think in worst-case scenarios and are taught aggressive use-of-force tactics, it’s not surprising that many of these calls, especially those where a citizen displays signs of mental illness, don’t end well

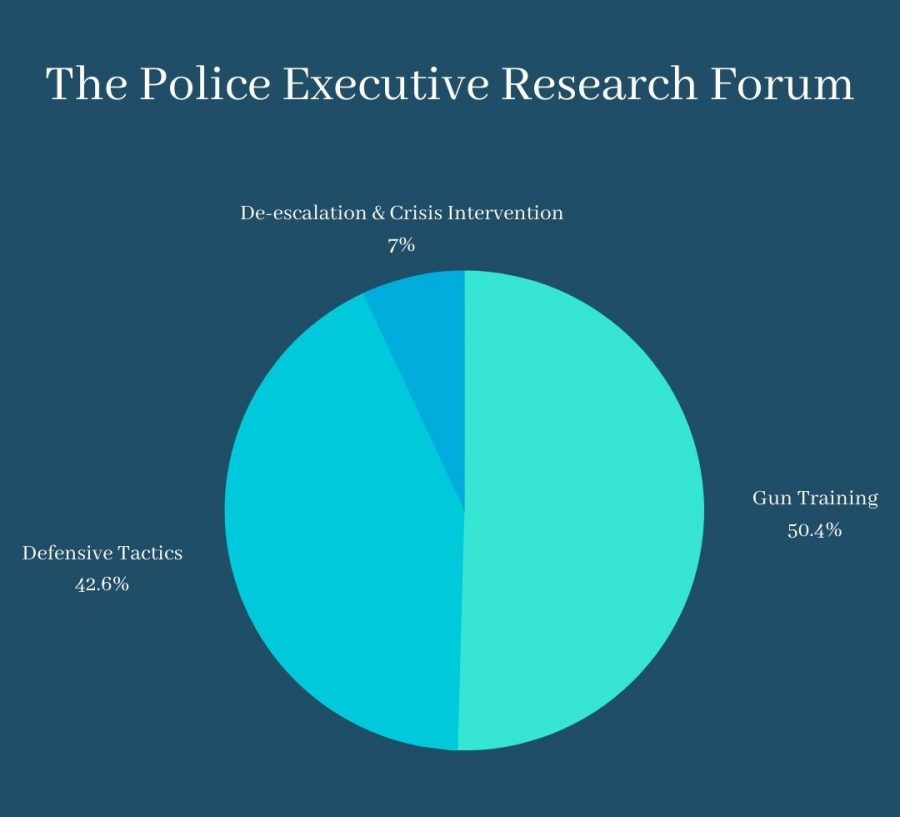

That means only about 7% of their time training is spent training for calls that are non-violent 90% of the time.

The Washington Post reports that in approximately a third of fatal police-involved shootings, de-escalation could have prevented the death.

In one study in an NYPD stop-and-frisk program, over 90% of the people stopped by the police were not breaking the law and had no drugs or weapons on their persons. Most of those who were stopped were Black and Latino, and physical force was used half the time.

What would defunding the police fix?

According to the American Civil Liberties Union, defunding the police entails cutting the enormous amount of money funding the police department and using that to fund other essential departments such as job training, housing, counseling, and violence prevention. Contrary to popular belief, it does not mean there will be no form of law enforcement.

The truth is, police officers are forced to deal with issues simply beyond the scope of their job description, and often that causes more animosity than it resolves. Calls come in regarding homelessness, mental illness, neighborly disputes, loud music, etc.

“We should be treating homelessness not with policing, but with housing. We should be treating addiction not with policing, but with treatment. We have dedicated so many of our public dollars simply to policing, and that hasn’t made us actually more safe,” said Greg Casar, a city council member from Austin, Texas.

The 2019 Pleasanton police department report showed psychiatric commitments as one of the top situations the police respond to, and even though the report also mentions a special enforcement unit to provide specialized responses, information is severely lacking.

“Police officers cannot be expected to be social workers, homeless outreach coordinators, and mental health experts, while also being law enforcement officials,” said Robin Hwang, a representative of a Pleasanton youth organization, at a city council meeting on July 31st, 2020.

Even retired Milpitas police officer Sandy Holliday concedes that police officers receive many calls that may be more suitably handled by another department. She admits that the workload and responsibilities laid on the shoulders of the police department are too large, but maintains that nobody can predict what will happen at the actual call.

“You might get a call with a mental health crisis, and they’ll request a social worker. But a lot of times, you get there and the call turns into something totally different. That’s my only concern. I am looking forward to the ideas that a lot of citizens and entities have about somehow transferring some of the duties so that officers can focus more on the violent calls,” said Holliday.

But Casar, Hwang, and countless activists argue that the aim of this transfer of funds to social workers and suicide prevention lines is to prevent the need for such calls in the first place.

If these agencies had the resources to better take care of their mentally ill patients, most times the police would not have to arrive at the scene at all.

What about Pleasanton, specifically?

When it comes to Pleasanton, here are the facts: the city budget has allotted about $30 million to the police department, 24.5% of our general fund, which is still higher than any other allotment, including general government, fire, and community development. Only $4 million goes to housing.

This distribution is, in the context of funding for police departments in other cities across the country, not entirely unfair. But the policies and history of the department are as disturbing as any other.

The Police Scorecard, a project started by Campaign Zero that examines a police department to give it a “grade,” assigned Pleasanton a D (63%).

The scorecard takes into account police violence, accountability, approach to policing, as well as the policies related to these issues.

The black population of Pleasanton accounts for a mere 5% of the town, and yet they make up 16% of arrests made by the police.

There are even still policies in place that make it harder to hold the police accountable, such as disqualifying complaints, limiting oversight/discipline, restricting/delaying interrogations, and giving officers unfair access to information.

We may be better off than other police departments, but our town is not exempt from racial bias and the horrifying effects of ingrained use-of-force training.

As quoted in Pleasanton Weekly, during a community listening session on policing, John Baur said, “There’s been three high-profile deaths at the hands of Pleasanton police: John Deming Jr., Shannon Estill and my son, Jacob Bauer. All three could have been avoided had the responding Pleasanton police officers acted differently.”

While many residents argue that the police department in Pleasanton has been exceptional, it’s important to understand their perspective and, to be frank, their race. Black and brown people, even in our community, have different stories to tell. It’s time we listen to them.

Whether or not defunding the police is on the books for Pleasanton, a thorough review of their policies and actions most definitely is. In fact, just in the last week, the Pleasanton council approved a policing policy review action plan with input from the community.

“In the past, for confidentiality reasons, a lot of policies weren’t made public, but now the public wants it, and a lot of the police chiefs, including Pleasanton, are saying ‘let’s open it up, and see what we can modify,’” said Holliday.

This is a step in the right direction.

Now more than ever, it is imperative that every single one of us asks ourselves this: is it morally justifiable for us to give as much power and unrestricted access as we currently are to the same people who have the authority to arrest, kill, or detain us oftentimes without any lasting consequences?