The Russian-Ukraine conflict and Anti-Russian sentiments in America

As Russia’s military actions in Ukraine are broadcasted in news all over the world, many people in Western countries have shifted the blame to the Russian people living in their countries.

May 2, 2022

Russia’s recent “military operation” in Ukraine has been condemned by Western countries as an invasion and led to many sanctions on the country from Western countries against Russia.

While these sanctions are aimed at the Russian government, sentiments against Russian people living in the west are increasing. Do these sentiments achieve anything to help end this conflict?

Russian actions in Ukraine were ordered by the Kremlin, but inevitably, many people in the US associate the Russian people with the invasion.

”In the first couple of days, people were asking what my position was on the topic of the war. I had to explain that the Russian people themselves have nothing to do with the conflict and have no effect on Putin’s decisions,” said a Russian senior student who asked not to be named.

Russians in the US had been experiencing many forms of hate based on their nationality. Many worry that they, having nothing to do with the government’s actions, would be blamed for the invasion by the western people or suffer “sanctions” by western institutions.

“In the midst of the conflict, the most concerning were the stories of people being rejected from colleges and denied job opportunities or scholarships because of the fact that they are Russian. It is especially concerning for me, personally, as it is my senior year and I am now starting to receive admissions decisions. I do not know if these stories are entirely true, but I suppose it is possible that these things actually happened,” said the anonymous senior student.

While there is not much evidence of colleges discriminating against Russian students, hate crimes have definitely been rising due to the conflict. The Pushkin Russian Restaurant in San Diego received bomb threats and 1-star reviews saying that the restaurant supports the invasion, even though it has donated to Ukraine and half of its workers are Ukrainian. Many other Russian restaurants across the country are experiencing similar hate and some were vandalized.

These examples of pure nationality-based hate shows widespread ignorance — people express hatred towards the wrong targets and often resort to violence, achieving nothing. This kind of hate has been around — Asians in the US experienced similar hate crimes during the Covid lockdown.

While most agree that hate crimes against Russians and Russian-owned local businesses are prejudiced and absurd, there is more debate over organizations like music institutions trying to “distance themselves” from anything related to Russia, such as by excluding Russian artists from concerts.

“I don’t think we should be boycotting Russian performers or Russian composers because of what Vladimir Putin has done. I think that the performers can make statements through music that they might not be able to in other ways,” said Mark Aubel, music director.

Many Russian musical artists in the west are facing canceled performances and backlash purely based on their nationality. Alexander Malofeev, a young acclaimed Russian pianist, publicly criticized the invasion and supported Ukraine. However, his performance in Vancouver was canceled by the Vancouver Recital Society.

“The last thing I wanted to do was bring a 20-year-old to the Orpheum in Vancouver and have it surrounded by protesters and have people inside heckling,” explained Leila Getz, director of the Vancouver Recital Society.

Even though Getz said that she felt horrible about the decision, many people feel that it is not justified. On what basis does she assume that the audience would heckle an artist who publicly condemns the invasion? The audience is there to see the concert, not express their opinions over the war.

“I have never seen so much hatred going in all directions… I still believe Russian culture and music specifically should not be tarnished by the ongoing tragedy, though it is impossible to stay aside now,” Malofeev posted on his Facebook page to express his disappointment.

Malofeev’s fans who had looked forward to seeing him perform were outraged by the cancellation, viewing it as a clear act of prejudice and discrimination.

“This is wrong. This is not what the world needs. Music and Art can heal the world, but this blind cancellation just hurts us all more,” commented a fan on Malofeev’s Facebook page.

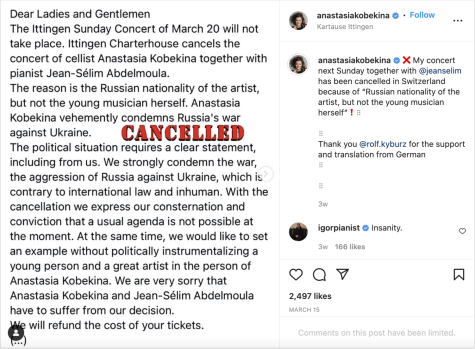

Sadly, Malofeev is one example out of many. Anastasia Kobekina, a Russian cellist who also publicly condemned the war, was barred from a performance in Switzerland. The organizer stated that “the reason is the Russian nationality of the artist, not the young musician herself.”

It is clear that people who made decisions to boycott Russian performers know that such actions are extremely unfair to Russians. Then why do they do it, and what do they hope to achieve?

“The extreme brutality of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demands, in my opinion, maximum isolation of Russia on all fronts in order to send a message to Putin that he has and will continue to irreversibly destroy his country and anything good about it unless he reverses course,” commented a reader on a NY Times article about boycotting Russian artists.

This perspective calls for harm on Russia in all forms, even discriminating against individuals. It certainly sends a powerful message, but it is one of hate and unacceptance, escalating tensions.

Or, the institutions are simply trying to save themselves. If they allow Russian artists to perform, they will certainly be connected to the war, even though the connection is distant. Unfortunately, it is unavoidable for the public to think of the war when they see anything Russian. So, the institutions firmly distance themselves from the controversy of the war at the expense of the performers.

On the other hand, some music institutions have been using their influences to raise awareness of the war. The Berlin Philharmonic, one of the world’s top orchestras, is hosting fundraising concerts featuring Russian and Ukrainian composers. This is an example of what institutions should do — rather than trying to distance themselves, they should advocate for inclusiveness and cooperation.

“I definitely think that music can be used to spread messages. Whether it’s the Ukrainian national anthem, which we are doing in choir right now, or pieces by Russian composers,” said Aubel.